On 1st October, a large sinkhole opened up in St Albans, UK, cutting off an entire cul-de-sac of houses. New sinkholes are very common, but this one quickly became international news due to its photogenic proximity to houses.

We think of sinkholes as appearing in places like Florida or the Yorkshire Dales. Why did one occur in St Albans?

Sinkholes can have a number of causes. The most common cause is the dissolution of rock or washout of loose soil to produce cavities (i.e. caves) which eventually collapse. This is more common in areas with soluble rocks such as limestones or evaporites (e.g. halite). Modern urban construction can alter the drainage in such a manner that urban sinkholes can occur in only a few years. Depending on ground conditions, leaky water mains have also been known to quickly produce sinkholes. When that unfortunately happens, professionals like the one on this anonymous post may be on the scene to address the issue.

A second cause can be due to the collapse of man made underground structures such as mine workings. Such collapses are the main cause of the small earthquakes found in places such as old coal fields or slate quarries.

Let’s have a look at some maps, to see if we can find some clues as to the cause.

This first map has been produced with Calper Maptitude and shows the British Geological Survey’s (BGS) Solid Geology map (imported as a WMS overlay): (click for larger view)

Central St Albans is located just off the bottom of the map. The location of the sinkhole is marked with a red X in a circle.

A ‘solid’ geology map like this one shows the underlying geology and ignores any overlying superficial deposits such as soil, peat or alluvium. The green is Cretaceous Chalk. Although people often do not think of chalk as producing sinkholes, it is still a limestone that easily dissolves, and it does produce hollows, caves, and other collapse structures. The orange is the Palaeogene Lambeth Group. This consists of clay, silt, and sand; and overlies the chalk.

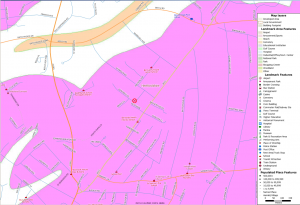

Here is the superficial map. This shows the upper layer of soils and river deposits: (click for larger view)

Here, the large area of pink is classed as the Kesgrave Catchment Subgroup. This consists of fluvial sands and gravels from the last 3 million years. The beige/orange band in the upper left consists of a mixture of river terrace deposits and recent (industrial revolution) earth works. Even though some of the media reports are talking about glacial clays, in reality all of these surface deposits were formed by rivers, and not glaciers.

From these maps, it looks like the sinkhole might have been caused by dissolution of the chalk, leading to a collapse of the overlying clays, silts, and sands.

From the information that has been made public, I think that has to be the leading theory. However, the existence of abandoned clay workings has also been mentioned in the press. The former heath to the south west of the sinkhole was worked in the 19th century for brick clay. Local archaeologists are citing this as a likely cause. Maps of pre-20th century mine workings are rarely very good, and a geophysical survey is currently attempting to find any hidden workings. The sinkhole could be due to the clay workings and it is possible they might find evidence that would clinch it – e.g. the hidden internal shape of the cavity, or the presence of pit props and other human artifacts. However, the geological maps would suggest that although clay is present, it is not extensive. Also the superficial deposits (sands, muds, clays) will lack strength, so limiting any tunnelling. Any clay workings were likely to be pits or possibly bell pits, and not true mines. A pit would only leave a cavity if it was poorly filled.

There is a third possibility: The old clay workings were filled with no cavities, but the combination of different fill materials, changes in suburban drainage, and a wet summer; allowed the fill to wash out, opening up a new cavity.

For now we shall have to await the findings of the geophysical survey and other site investigations. I’ll post any updates as I get them.

This week as a part of Earth Sciences Week, the Geological Society are running their “Ask-a-Geologist” feature as a live event on Twitter.

Tomorrow (13th October), Dr Helen Reeves will be answering questions on sinkholes! Use the hashtag #askageologist on your tweets. Dr Reeves will be answering questions between 10:30 and 11:30am UK time.

Thanks to Kirsten Tisdale for pointing me to an update at the BBC: http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-beds-bucks-herts-34639340.

The results of the initial geophysical survey are in, and it would appear that there’s another cavity extending from the area that has been filled in.

The site is described as being a claypit that was backfilled in the 19th century. For such a large amount of the backfill to collapse like this, there must have been somewhere for it to go. The site investigators believe there was probably a chalk excavation that the backfill has collapsed into. This could well have been a very slow process – it being over a hundred years since the original backfill, although recent rains could have speeded it up.